BY RICK RADER, MD “There comes a time in a man’s life when to get where he has to go – if there are no doors or windows he walks through a wall.” – Bernard Malamud

Some things sometimes get the limelight that others deserve. Take the device that enables efficient movement of an object across a surface where there is a force pressing the object to

the surface. The “wheel” is heralded as one of the world’s greatest inventions. But, in reality, it is simply a circular component. In fact, without its counterpart the “axle” it is relegated to being a doorstop (the role of the door is for another article). The wheel gets all the limelight while the axle gets a mere footnote. The wheel with its axle changed the world as we know it. The wheel and axle is one of the “simple six machines,” the others being the lever, the pulley, the inclined plane, the wedge and the screw.

Washing clothes is another example of a tandem act. For centuries, all you needed to clean clothes was a flat rock and a stream of water. The drying was left to the sun and the wind. The appearance of the washboard in 1797 was a milestone and was easier to transport than a rock in a

stream. Early washing machines were steam driven and the electric washing machine made its first appearance in the early 1900’s. So washing clothes with a purposeful machine was becoming commonplace while the drying process was left to hand wringing, hanging them over

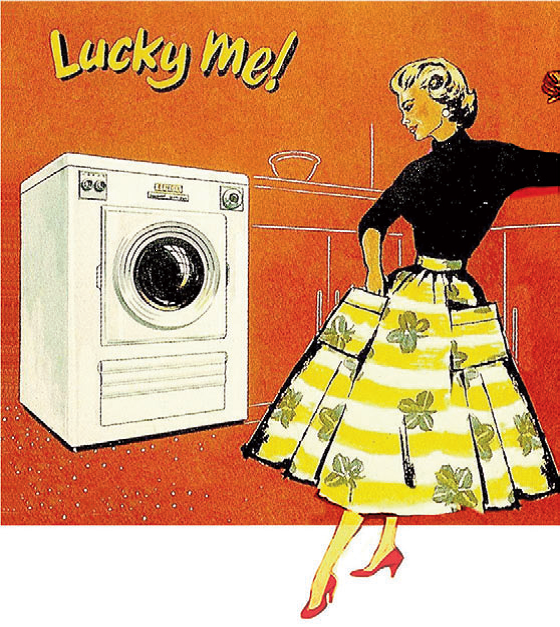

rocks, tree branches and clotheslines. While the electric clothes dryer was introduced in 1915, it was not until the Hamilton Manufacturing Company produced the first automatic dryer in 1938 that the use of the dryer started to become known.

Hamilton’s engineers had developed a plain metal box with an electrically powered rotating drum inside and equipment for gas heating. Except for an on/off switch, the machine was featureless and lacked any appeal or soul. The company was having trouble selling the dryers because people did not know how they worked. Hamilton hired Brooks Stevens, an industrial designer to address the problem.

After spending some time in a room with the clothes dryer, he reported to the sales team, “You can’t sell this thing. It’s just a sheet metal box.” Stevens suggested putting a glass window in the front and loading it with the most brightly colored boxer shorts the manufacturer could find for demonstrations in department stores. That window, that glass porthole allowing people to see “the works,” was translated into record breaking sales. That 1940’s “window” is still the centerpiece of today’s modern clothes dryers. In 1954, Stevens coined the phrase “planned obsolescence,” as the mission of industrial design: “Instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.”

The porthole on the dryer was indeed, “newer,” “better,” and “sooner.” The need to see how things work is hard wired in humans. It is the basis of knowledge gathering, problem solving, improvement science, innovation and progress. Case in point: Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm. First introduced in 1956, Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm is a toy industry icon that has delighted generations of families. It allowed children to “see” the underground world and activities of ants through an “observation tank” not unlike a home aquarium. One of the most popular toys was a line of “visible models.” Children were intrigued by assembling models of “humans,” “horses,” and “car engines” with clear plastic covers allowing them to see the parts, their relationships and how they interacted. The early introduction of the “visible models” in early education influenced thousands of children in pursuing careers as physicians, veterinarians, scientists and engineers.

The desire and intrigue to see clothes tumbling as they dry, or to understand what is going on inside the box, is the same human drive to understand decisions made that influence and impact the lives of individuals and families (and communities) confronted with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Parents, families, advocates, educators, researchers and professionals are often confounded by policies, mandates and regulations that seem to miss the whole point.

The point is, has been, and always will be that our communities, our lives, and we ourselves, benefit from a culture, an environment and a landscape that value the merits and contributions of each and every one. And while we were always allowed to see how soiled clothes were cleaned by being slammed and pummeled against a rock, as the process progressed to taking place in a sheet metal box, we were perhaps both intrigued and mistrusting about the “process.”

The American novelist Bernard Malamud sensed the need for us to have window vision, “There comes a time in a man’s life when to get where he has to go – if there are no doors or windows he walks through a wall.” Walking through walls is exactly where exceptional parents have walked to see how things work… or don’t work. Exceptional parents deserve and demand transparency in the creation of policies that can either support or hinder their lifelong struggle to insure that their children, across the lifespan, have opportunities that celebrate their personhood.•

ANCORA IMPARO

In his 87th year, the artist Michelangelo (1475 -1564) is believed to have said “Ancora imparo” (I am still learning). Hence, the name for my monthly observations and comments.

— Rick Rader, MD, Editor-in-Chief, EP Magazine Director, Morton J. Kent Habilitation Center Orange Grove Center, Chattanooga, TN